The circular economy movement is one of the biggest ideas in sustainable thinking at the moment. At its most basic, it says that we should close the loop. We are now in a mostly linear economy, where you take resources, make a product, use it, and throw whatever isn’t consumed away, including a whole bunch of one-use packaging. In a circular economy, we would design things so that they can be fully reused, either in the same form, like packaging, or with modules that could be taken apart and reshaped. We would also find ways to reuse things that are currently wasted and not throw away goods while they can still be used. Eventually, the idea goes, almost everything would be made so that there would be very little wasted. The only things consumed would be ones that can be regrown in a regenerative way.

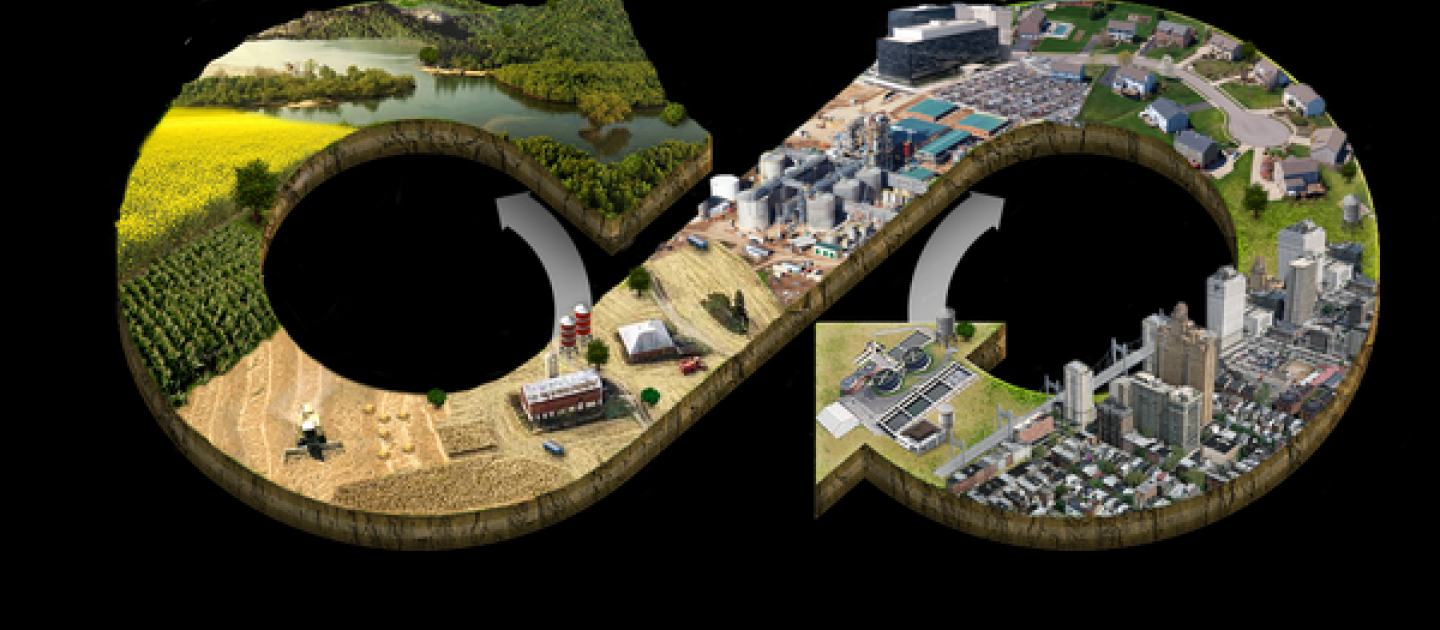

This is an overview of the idea:

For a much more detailed look, there’s a good and often-used infographic at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, one of the main proponents of the idea.

It would be a wonderful way to make sure we could continue to live, and would have undeniably positive effects on resource use, waste and emissions. And there is a lot of work being done to explore how to make it happen. The problem is that little of that work seems to consider human behaviour.

For example, at last week’s World Circular Economy Forum in Helsinki there was one side session (not part of the main conference), on “Consumer and behavioural insights into the circular economy”, which basically pointed out that nothing is currently being done and that they’re setting up a panel to get that started. The rest of the conference was about business, technology and policy, even the parallel session on “Circularity in our day-to-day lives”.

It was the same story during the 2019 Week of the Circular Economy (January 14-18) here in the Netherlands, a country considered to be at the forefront of the movement. There were roughly 120 events throughout the country during the week, highlighting a lot of really cool initiatives, all about reusing materials, redesigning cities and housing and financing and designing a circular transition. But there was just one workshop (part of a bigger event) that I could find that talked about behaviour change at all.

There is also no explicit mention of looking at human behaviour in a circular economy on the websites of major organizations in the field such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation or Circle Economy.

It seems like nobody’s thinking about what will happen if they build it and people don’t come.

I think that one reason that many circular economy folks haven’t explicitly considered the place of behaviour change is that they think the other changes will in themselves be enough. They think that humans will react as rational deciders to the changes that are made, either because the new solutions are objectively better, or because policies and incentives make them more attractive. If this is the case, all they need to do when the pieces are there is make sure they are rationally the best option and that people are aware of them.

This is the sort of thinking that informs one of the few studies I can find into the problem, a recent EU report, Behavioural Study on Consumer Engagement in the Circular Economy. The study was set up to look at barriers and trade-offs for consumers in a circular economy and the relative importance of economic, social and psychological factors influencing engagement and to suggest solutions. It’s 200 pages covering literature review, stakeholder interviews, focus groups and survey results. Some survey respondents also answered questions for an “experiment” involving future hypothetical repairs.

They found that most people are very willing to engage in circular economy (CE) practices, but their actual engagement is low and that people are more likely to look for a durable product, or repair or lease it, when it’s an expensive and non-fashion dependent product. Their recommendations are pretty standard: strengthen pro-environmental attitudes/awareness, make repair easier through design, use financial incentives, provide durability/reparability information and enforce legislation around provision of accurate information.

The problem with the report is that they assumed that self-reports and reactions to hypothetical situations would give an accurate view of behaviour. They didn’t test anything or look at real world situations in real time. And when the hypothetical questions gave a glimpse into a non-rational response, they ignored it and used it to bolster their economic philosophy.

This hypothetical situation was meant to test framing on the consumer willingness to repair. It involved listing repair prices as VAT (sales tax) exempt or not (while keeping prices constant). They found that the framing hardened choice: those who were pro-environmental became more likely to repair when the repair was VAT exempt, and those who were most into trends and fashion became even less likely to repair. However, because the two groups cancelled each other out, the overall willingness to repair stayed the same, and the researchers concluded that framing didn’t have an effect and that findings were “in line with what classical economic theory would predict.” (page 103).

To me those results actually prove the opposite and raise questions that should be answered. What caused the hardening? Did framing it as VAT free signal government or mainstream (non-fashionable) pushes and thus make it less desirable for some, while confirming the choice for those who agreed with the government’s perceived environmental goals? Was it something else entirely? Would variations in the framing have the same or different results? Would another frame altogether work better?

What their conclusion also tells me is that that they fell prey to just the sort of biases that they are implicitly arguing against by calling consumers rational. Their interpretation of the results confirmed their initial belief to them, that “as economic agents, consumers tend to be rational when making purchasing decisions” (page 70), which then informed the recommendations. If you believe that consumers are rational, the strategy they proposed should work.

The problem is that it doesn’t and they aren’t. We think they are rational because we think we are, but we’re really, really not and neither is anyone else. We’re subject to framing effects and a whole slew of biases and so much more, all of which is pretty well documented by behavioural economics and nudging sources. We make a lot of decisions without even noticing and we’re subject to social norms and habits and what we always do. We’re really not “rational economic consumers” most of the time.

The idea of the rational consumer dies hard though. Even when I wrote my MA thesis in the early 2000s there was a lot of research that proved that attitudes did not predict actual behaviour, that providing information did little to change it and that there were a lot of better strategies. A few people were using them, but not very many. With the publication of Nudge in 2008, the founding of the Behavioural Insights Team in 2010 and the publication of Thinking Fast and Slow in 2011, using research that shows how humans actually behave started to become more of a normal thing. But, as we can see with the circular economy, this is a hard myth to kill.

I have found two groups who seem to be giving it a try. One is the new research group Psychology for a Sustainable City at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, which is brand new and doesn’t even have an English website yet. The other is the Collaborating Centre on Sustainable Consumption and Production (CSCP), which hosted the side session I mentioned above. But as far as I can tell, any work there is in the beginning phase, just getting people to realize, as the CSCP said at that side session:

Their work, and the work of many others will be needed to make the circular economy a reality. Because in the end, almost everything comes down to people and choices. People are the ones who buy things, use them, re-use them, recycle them, and discard them. People work for companies, people work for governments. People design things, people make things, people run companies. People make policies and run programs. Governments are people. Economies are people. And people just aren’t rational.

So, what should circular economy folks be doing differently? Keeping in mind that everything is people and that people aren’t rational is a good first step. Don’t assume that you know how people will respond to something or that the benefit will be self evident. Think about whether your solution can make things easier and more attractive for people. Think about the role of social norms. Think about the need to break habits. Look at nudging. Above all, test it on actual people. Test variations and see which works better to get people to adopt. Test against a control group if possible, randomized even better. And then change it in reaction to what you find to see if you can find something that works better. After all, if nobody uses it, does it matter if it exists?

Through Google, I did find a few other papers on behaviour change and the circular economy, although nothing where behaviour change strategies had actually been used or tested. I’d love to see it if it is out there. Of what I did find, this article discusses the non-rational role of consumers in business strategies. This masters thesis looking at Theory of Planned Behaviour and circular economy, though his research only looks at increasing the intention to participate, not actual behaviour. This paper (which I couldn’t access fully), also only looks at using communication to change intention to participate. Then there are a couple papers calling for design to change behaviour, saying more research is needed, and a simple call to do it. Finally, the EU’s platform for good practices, lists 38 (out of the total 227 projects on the site) that say they include behaviour change, but none of them seem to be behaviour change interventions, more projects that would require behaviour change.

Source of header image: UN Environment